Drivers snake their way through Times Square this summer. Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

This article was originally published by The CITY on Aug. 10

The years-long effort to toll vehicles in the most congested parts of Manhattan as a way to bankroll billions of dollars in mass-transit improvements and reduce traffic is no longer stuck in neutral.

Today officials released the long-delayed “environmental assessment” of the proposed Central Business District Tolling Program — touting how it could potentially cut congestion coming into the core of Manhattan by nearly 20%, improve air quality, boost bus service reliability and increase mass transit usage.

The document also outlined what the program may cost drivers entering the toll zone: between $5 and $23 per trip, depending on the time of day and the type of vehicle.

The shift would change truck traffic in Manhattan, in particular; the report estimates truck trips through the central district would drop between 55% and 81% as drivers opt for less expensive routes. But it acknowledged that tolls could increase the number of drivers diverting onto roads in the South Bronx and on Staten Island.

Initially approved in 2019 by then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the state legislature, the rollout of so-called congestion pricing has been repeatedly hampered by federal bureaucracy, including hundreds of highly detailed questions from the feds that pushed back the projected launch date.

But the program that aims to fund $15 billion of subway, bus and commuter rail improvements as part of the MTA’s 2020 to 2024 Capital Plan now appears to be on track, with virtual public hearings set for later this month.

“Bottom line: this is good for the environment, good for public transit and good for New York and the region,” Janno Lieber, MTA chairperson and CEO, said in a statement.

In hundreds of pages made public early today, the Federal Highway Administration, the MTA Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority and the city and state transportation departments detailed how congestion pricing could reduce the number of vehicles entering Manhattan’s central business district between 15% and 20% — and also help the struggling mass transit system.

Midday traffic rolls down Seventh Ave in Midtown this week. Hiram Alejandro Durán/THE CITY

“Millions of riders are counting on a rapid, robust congestion pricing program that delivers essential reliability and accessibility upgrades,” said Danny Pearlstein, policy director for Riders Alliance, an advocacy group. “It can’t happen soon enough.”

For Whom the Bill Tolls

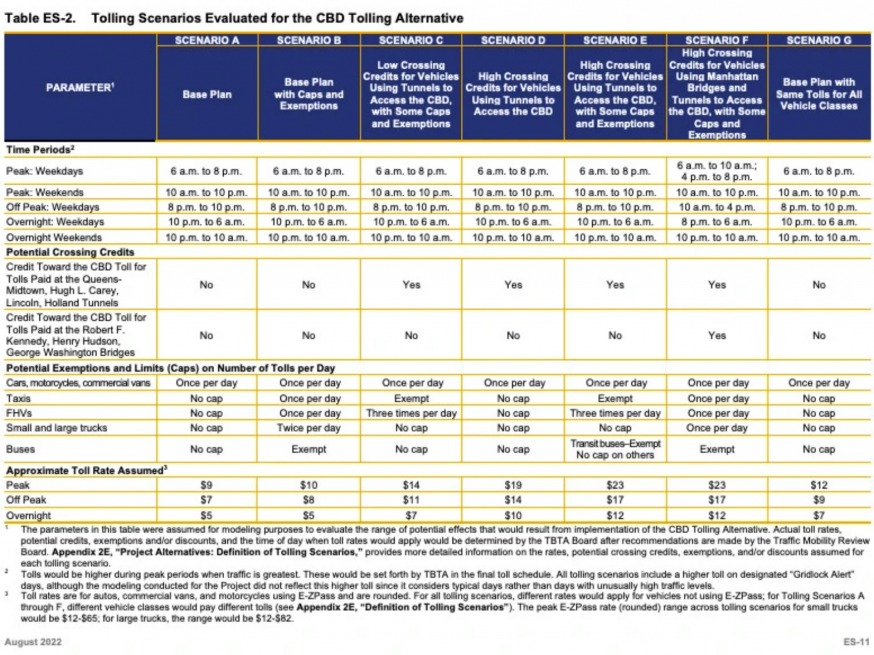

The assessment spells out, in seven different tolling scenarios, how much motorists may have to pay to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street — with potential rates for non-commercial vehicles ranging from $9 to $23 during peak periods and from $5 to $12 during the overnight hours.

Different vehicle classes would pay different tolls, with the peak E-ZPass rate for small trucks ranging between $12 and $65. For small trucks with E-ZPass, the peak rate could be between $12 and $82.

Overall, about 95% of drivers passing through toll stations run by the MTA use E-ZPass, according to a senior MTA official.

Commercial drivers are wary of the added costs.

“It will impact my company,” said Constantine Savagious, 37, an HVAC technician who was unloading a truck near Penn Station. “They will likely raise the rates for clients who hire them.”

Seven tolling scenarios, from the multi-agency summary of the congestion pricing environmental impact statement. MTA

Tolls would also be higher, officials said, on city DOT-designated “Gridlock Alert Days,” which typically coincide with occasions such as the United Nations General Assembly and the holiday season.

The 2019 state law that spurred the current iteration of congestion pricing made three categories of drivers exempt from the tolls: Emergency vehicles, vehicles transporting people with disabilities and any vehicle belonging to families living inside the Manhattan congestion pricing zone in which the household earns $60,000 or less per year.

State Sen. Leroy Comrie (D-Queens), who oversees a committee with oversight of the MTA, pushed back in January against other proposed breaks, saying “there should be no exemptions.”

But a New Jersey Congressman has threatened to “defund” the MTA’s use of federal dollars unless Garden State motorists receive credit for tolls.

The MTA’s environmental assessment outlined some additional potential loopholes, including one scenario that would exempt taxis, but not for-hire vehicles like an Uber car. Two of the seven scenarios exempt taxis from tolls, and three of seven scenarios exempt city buses. (In the cases where buses are tolled, the MTA would effectively be paying itself; revenue from those fees would move from the MTA’s operation budget into its capital budget, which pays for big infrastructure projects, a senior transit official said.)

The documents spell out the impact of congestion pricing on everything from subway stations expected to take on more riders because of reduced traffic to an expected drop in revenue for yellow taxis between 0.3% and 5% in the New York metro region.

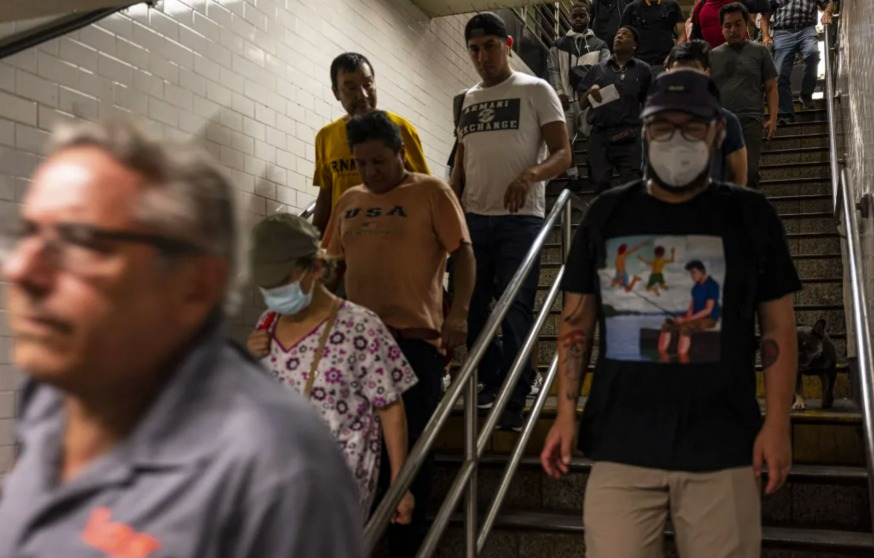

The ripple effects of congestion pricing could affect how riders move through subway stations like Times Square, shown here this week. Hiram Alejandro Durán/THE CITY

Since 2009, all taxi trips have included a 50-cent surcharge to help the MTA. In 2019, a $2.50 congestion surcharge was added to all taxi trips south of 96th Street in Manhattan. Drivers of for-hire vehicles, such as Uber, limousines and green taxis, pay $2.75 per trip.

MB Hosain, a cabbie for 15 years, said congestion pricing could help unclog city streets, but worried it will also drive away passengers from hailing trips on taxis.

“They will see the price on the meters and decide they want to come out of the car because the trip is too expensive,” said Hosain, who was waiting to pick up fares on the Seventh Avenue taxi line outside Penn Station.

Bhairavi Desai, executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, said congestion pricing would be “absolutely crushing” for a transportation sector struggling to bounce back from the pandemic.

“Another congestion surcharge would mean drivers are working to pay taxes rather than to earn an income,” Desai told THE CITY. “It’s a debtor’s prison.”

Faster Subway Escalators?

At some subway stations — including Court Square and Flushing-Main Street in Queens and 14th Street-Union Square and Times Square-42nd Street — the assessment found that an expected shift of drivers to mass transit “would affect passenger flows with the potential for adverse effects” at certain staircases or escalators.

At Times Square-42nd Street, if ridership increases during peak period, the MTA may have to remove a center handrail from the staircase between the station mezzanine and the uptown platform for the 1/2/3 lines.

To keep up with an expected influx of riders at the No. 7 line’s Queens terminal at Flushing-Main Street, the assessment notes that the MTA would have to increase the speed on an escalator connecting the station mezzanine with the street from 100 feet per minute to 120 feet per minute.

“In the case of Flushing-Main Street, there is an escalator that would be affected, depending upon scenario,” the senior MTA official said. “And again, we have a mitigation.”

The same speed increase could also be needed at a 14th Street-Union Square escalator that connects the L line’s platform to the mezzanine inside the sprawling subway complex.

Rachael Fauss, a senior research analyst with Reinvent Albany, told THE CITY that congestion pricing is “urgent” for a transit system that has more than $50 billion of upgrades planned as part of the current five-year capital program. The watchdog group has said the plan is off to a notably slow start.

“The MTA originally budgeted to have congestion pricing revenues start arriving in 2021, so getting funding in ASAP remains urgent,” she said. “It is also exactly the type of reliable, environmentally beneficial revenue the MTA needs to fund its capital program.”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.